In theory, March Madness should be the happiest time of the year for a website like this. Considering this is the first normal Tournament since 2019 – all games have been played, nothing has been cancelled, and full crowds are allowed in all arenas – it should be a time of celebration. To boot, the 2022 NCAA Tournament has produced 12 upsets (a seed difference of 5 or greater), which will go down as tied for fourth-most in Tournament history barring a North Carolina win or two in the Final Four. Everything should be feeling better. So why have I had this nagging feeling that I’m watching maybe the single worst NCAA Tournament of my lifetime?

Let me explain it this way: of course a site centered around Tennessee basketball complaining about a bad NCAA Tournament is going to sound like sour grapes. But I’ll cut you off at the pass. This analysis is mostly objective, even though I’d also say this has been the least satisfying NCAA Tournament in a long, long time. (TL;DR: Upsets are only useful the first two rounds, and the four remaining teams have a combined 7% likability. I’d trade any of them for Houston, Gonzaga, or even blue blood UCLA.) How could a statistician feel positive about an NCAA Tournament producing stats like these?

There have been 35 NCAA Tournaments since the three-point line was introduced in 1987. The 2022 NCAA Tournament is…

- 27th in points per game at 68.6 (2012, 65.7);

- 33rd in offensive efficiency (numbers pre-1997 are estimated) at 0.996 PPP (1999, 0.988 PPP);

- 34th in FG% all time at 42% (1999, 41.9%);

- 34th in eFG% all time at 47.7% (1999, 47.6%);

- 34th in Scoring Percentage (i.e., how many possessions end in some amount of points) at 44.5% (1999, 44.2%);

- and, worst of all, 35th in 3PT% at 31.5%.

The only thing this Tournament has done at an elite level that isn’t a bad elite thing is limiting turnovers (15.5% of all possessions), but that also leads to the lack of excitement. Turnovers are lower than ever and offensive rebounds are similarly at a Tournament-long valley, which means a lack of events. Coupled with the lack of made shots, it’s made for a lot of boring basketball. The median Tournament game has been decided by nine points, which is a hair lower than usual, but this Tournament has also produced eight games where the winner has scored 59 or fewer points. This is all before you get to the usual attractors: no buzzer-beaters, no true Instant Classics after the first day of the Tournament (Arizona/TCU, maybe?), not even many elite players still playing. (Among the 10 players in KenPom’s Player of the Year ballot, just one – Paolo Banchero – is still alive in this Tournament.)

No matter how you slice it, this has been an underwhelming, brick-filled Tournament. Naturally, I had to ask a lot of people smarter than me why. I polled several coaches and media members, giving them anonymity in return for what they thought was the reason for this particularly defense-friendly Tournament. I’ve divided up their responses into five theories, along with a sixth I’ve explored for my own good. Can I promise an answer? Not really. But I can promise that your theory of choice is probably listed on here somewhere, and I have tried to see if it makes sense or not.

Are players taking too many threes?

I’d be interested to know the percentage of threes taken in this tournament compared to past. Maybe too much reliance on the three?

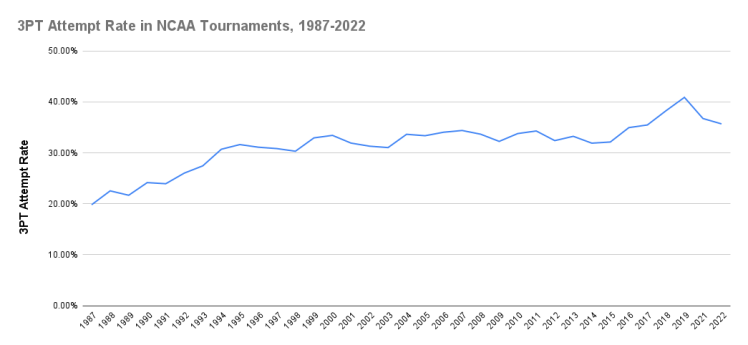

Is the three point attempt rate higher than before?

This one is fairly simple to answer: not really. Actually, for once, three-point attempt rate is going in the other direction. In one aspect, this theory could reasonably be accurate: the 2022 NCAA Tournament has the fourth-highest three-point attempt rate in March since the three-point line was standardized in 1987. That’s pretty big; take a look at the below graph and you’ll see just how big it is.

In fact, you can see a pretty good story with it. In 1994, the 3PA% breached 30% for the first time in March, and it never dipped below 30% again. It held somewhere between 31-34% for 22 years, until finally, in 2016, we hit 35% or higher for the first time. My guess is that it never goes below 35% again. However, you can see that we’ve possibly hit Peak Three with the 2019 NCAA Tournament, the only one to ever have an attempt rate above 40%. This year represents a regression of sorts to the 2016-2017 NCAA Tournaments.

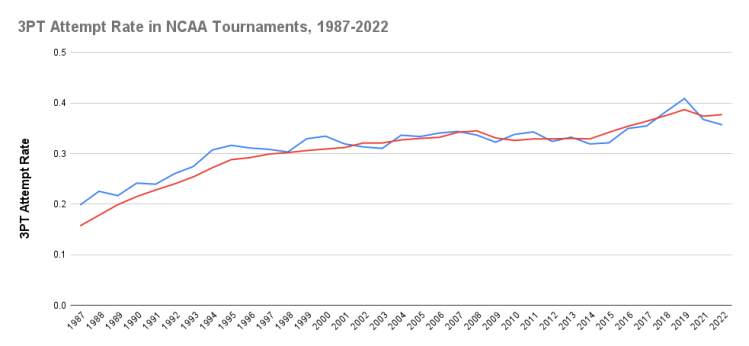

The other intriguing part of this: matching the postseason three-point attempt rate with its larger sample-size brother, the regular season.

There’s a serious part of your story: teams are taking fewer threes in the postseason than they did from November to early March. Three-point attempt rate in March is still pretty close to the regular season rate, but the 2022 NCAA Tournament tells quite the story: only the 2015 NCAA Tournament has a greater decrease from regular season attempt rate to postseason attempt rate. Teams are taking 2.01% fewer threes in March as of now.

In theory, you could explain part of this drop by noting that fewer three-point heavy teams made the field this time around. Among the NCAA’s top 35 teams in 3PA%, only two made the field: Alabama and Villanova. Alabama bombed out early, but Villanova is still playing, so maybe this isn’t the best test case. Still, think of it this way: if you apply that same “top 35 in 3PA%” query to previous years, five Top 35 teams made it in 2021, six in 2019, and five in 2018. We just had an unusual dearth of high-3PA% teams this year. Then again:

Median 3PA% of NCAA Tournament Field, Last Five Years

- 2022: 37%

- 2021: 36.9%

- 2019: 38.5%

- 2018: 37.3%

- 2017: 36.4%

If anything, this Tournament should have had marginally more three-point attempts than last year. And yet: that graph above shows it’s the lowest 3PA% since 2017. So: I don’t think it’s the volume of threes, necessarily. Maybe it’s the quality?

Are the wrong players taking the shots?

Players that don’t shoot the three well enough are embracing the revolution by shooting more threes than they typically do . This has caused an influx of three-point attempts, but the percentage of makes across the entire NCAA drops because these new shooters aren’t shooting at a good enough percentage.

Guys who should not be taking threes are taking them.

I’ve broken down the concept of the Right Shooter™ as follows: a player who hit 34% or more of his threes in the regular season (AKA, above the national average of 33.7%) while taking 45 or more (AKA, roughly 1.5 or more a game). That gave us a sample size of 187 players across 68 teams to work with, or roughly 2.67 per team. I think this lines up with a subjective view of the game: the average NCAA Tournament team has about 2-3 guys you’re happy with taking whatever they want to take from three, followed by a lot of coin-flips or no-gos on the rest of the roster.

The best way to compare this is to show what these guys did in the regular season. Across a data set of 187 players, this group went 9428-for-24284 on threes, or 38.8%. Every other three-point attempt by NCAA Tournament teams: 7343-for-23483, or 31.3%. That’s a huge difference: 1.164 points-per-shot versus 0.939. You’d much rather have the Right Shooters take these shots than the Wrong Shooters. Something else you’ll notice is that our Right Shooters took 50.8% of their team’s three-point attempts on average; everyone else got slightly less than half. Again, seems right: 2-3 shooters getting just over half the deep balls tracks mentally.

What’s left to prove, or disprove, is if these splits held up in the 2022 NCAA Tournament. Here’s how it’s held up in March:

- Right Shooters™: 53.1% of all three-point attempts; 32.9% 3PT%

- Wrong Shooters™: 46.9% of all three-point attempts; 30% 3PT%

Interestingly, teams’ best shooters are actually taking a hair more of the share of three-point attempts than they did in the regular season, at 53.1% vs. 50.8%. The problem: the best shooters have gone dead cold this March. Collectively, those 187 players, which include some of the best shooters in America, are shooting 5.9% worse in this three-week sample size than they did across the regular season as a whole. It’s the Wrong Shooters that are more in line with expectations, at 1.3% below.

So: it’s not that bad shooters are necessarily taking more shots, really. It’s that the best shooters are failing to produce the best results in the spotlight, and teams frequently have nowhere else to turn. Why could this be so?

Is there more switching defensively/better defense in general?

The defense has been outstanding [this Tournament]. Hard to get open looks.

Much more switching defensively than in years past both on and off the ball makes it harder to create advantages which generate open looks. Length across the board in college basketball is at its highest level both in standing height and wingspan, which makes everything more difficult, including shooting and finishing.

Yes and no. I think this is pretty hard to measure with straight-up metrics. Subjectively, you could say “yes” and not many people would really blink at it. Per Patrick Stevens, this has been the most defense-friendly Tournament in years:

What makes that stat even worse is that the number is now eight, after Villanova’s 50-44 defeat of Houston, with three games still left to play. The possibility of one final stinker still exists. Stevens only goes back to 2011, but eight sub-60 winners is tied with 2006 for the most Defensive Battles™ in the shot-clock era (36 Tournaments strong). You’re watching the fastest Tournament by average tempo (68.6 possessions per game) since 2003, but simultaneously the lowest-scoring Tournament since 2015. What gives?

A popular theory, among nearly everyone I talked to, is that the defense is just straight-up better this March than usual. There’s a few different ways of looking at this that could help things make sense. If you want to see if more high-end defenses made the Tournament than usual, you can look at this and say…no, actually:

Percentage of Top 30 Defenses That Made NCAA Tournament:

- 2022: 26/30 (86.7%)

- 2021: 26/30 (86.7%)

- 2019: 26/30 (86.7%)

- 2018: 22/30 (73.3%)

- 2017: 22/30 (73.3%)

If you prefer the median NCAA Tournament defense:

Median NCAA Tournament Team’s Defensive Efficiency:

- 2022: 95.9 Adj. DE

- 2021: 94.1 (!)

- 2019: 96.6

- 2018: 98.1

- 2017: 96.6

You could look at that and say that, yes, this is a pretty strong defensive Tournament. And yet: shouldn’t 2021 have been far more defense-friendly if that were the case? The 2021 NCAA Tournament ranked 19th out of 35 NCAA Tournaments in terms of offensive efficiency; in the KenPom era (2002-pres.), it ranks 14th of 20. Not a great offensive Tournament, really, but certainly better than this one. Along with that, despite having the worst defenses in the sample size, 2018 actually ranks second-worst among the last five Tournaments in terms of efficiency.

One final way of attempting to answer this is through Synergy data. Like anything that requires human eyes to log statistics, Synergy’s data is subjective to the viewer. Still, it’s the best publicly-available database out there that is even somewhat comparable to Second Spectrum for the NBA. The best way of using it for this purpose is to take their Guarded/Unguarded data, as well as what they have for pull-up (off-the-dribble) jumpers, and see what it says.

In the regular season this year, Division I basketball teams shot 32.1% on guarded catch-and-shoot threes, which is any spot-up three where a defender is within four feet on the shot. (Synergy may deem this differently, but it is what I’ve always taken to mean an open vs. contested attempt.) On open catch-and-shoot threes, the D-1 average was 37.4%. Clearly, being open makes a difference: over the course of 100 three-point attempts, you’d hit about five more ‘open’ ones than you would ‘guarded’. Some teams are great (Villanova) or terrible (Wisconsin) at shooting against any sort of guarding, so, again, subjective.

Still, we could use that in three purposes: to determine if teams are simply missing a bunch of catch-and-shoot threes in March, to see if there are more guarded attempts than normal, and to see if teams are getting fewer catch-and-shoot threes period.

Catch-and-shoot threes, regular season versus NCAA Tournament:

- Regular season: 34.6% 3PT% on all C&S threes; 37.4% open; 32.1% guarded

- NCAA Tournament: 33.8% 3PT% on all C&S threes; 37.8% open; 30% guarded

Guarded vs. unguarded threes, regular season versus NCAA Tournament:

- Regular season: 53.4% Guarded, 46.6% Unguarded

- NCAA Tournament: 52% Guarded, 48% Unguarded

Average number of catch-and-shoot threes per game, regular season versus NCAA Tournament:

- Regular season: 15.8 combined per game (8.4 Guarded, 7.4 Unguarded)

- NCAA Tournament: 14.5 combined per game (7.5 Guarded, 7 Unguarded)

There’s a lot to take from this. Firstly, teams are having a horrific time hitting guarded catch-and-shoot threes this March. 30% on guarded ones is what Nevada, who ranked 247th in guarded FG%, shot in the regular season. That’s pretty bad. But the fact that the sport as a whole is down 0.8% on these shots (admittedly in a smaller sample size) is pretty interesting. Along with that, there have been fewer catch-and-shoot attempts in the postseason by a significant margin…but said catch-and-shoot attempts have also been slightly more open.

Subjectively, you could say that this has been a fantastic defensive Tournament, and it would be hard to disagree. At the same time, take a look at Ken Pomeroy’s pre-Tournament rankings on March 15. Zero top 10 defenses made the Final Four. In fact, none of the top 25 did: Villanova, at 28th, was the best defense before the Tournament started to be one of the last four standing. How much does defense matter in terms of stopping opposing threes? Pomeroy’s research, spilled onto this page several times over, notes that teams can prevent three-point attempts, not makes as frequently. The field of 68 has done a good job of this, but it alone would not explain the worst 3PT% in Tournament history.

Is shot selection worse than usual?

I think decision making [this Tournament] is very poor. Kids are trying to finish drives at the rim over length vs. playing off 2 feet and making a play for their teammate on a drive and kick. Tons of tough long twos as well – poor shot selection leads to poor FG%.

Thankfully, this one is a little easier to measure. In the regular season, teams got 35.5% of all shots at the rim, 26.8% in Other Twos territory (not a layup, dunk, or tip-in, but still a two), and 37.7% threes. I’ve done private work in the past for teams that shows the percentage of Other Twos increases by roughly 4% when playing Top 100 opponents versus playing everyone else, and one would expect that to more or less hold in a Tournament that mostly contains Top 100 opponents.

Still: I think this one has real merit. The average attempt at the rim in half-court offense, per Synergy, went down at a 55% rate. (Per Hoop-Math, this is 59.3%, but I don’t have the ability to split by regular season/postseason on there.) In the NCAA Tournament, this conversion rate has fallen to 53.5%. Makes sense; you’re playing tougher opponents in general. Has the theory held up for shot selection?

- Regular season: Rim 35.5%, 3PA 37.7%, Other Twos 26.8%

- NCAA Tournament, per CBB Analytics: Rim 32.6%, 3PA 35.7%, Other Twos 31.7%

The CBB Analytics work is of particular note, because it hammers in something that’s felt very real while watching the games. Per their data, 10% of all shots have been 16+ foot two-point jumpers, the least-efficient shot in college basketball. 18.3% of all shots have been two-pointers outside the paint. (There’s an array of runners, floaters, paint jumpers, post-up turnarounds, etc. that fall in the Other Twos category, too.) These rates are +2.6% and +4.6% above their regular season counterparts. So, yes: shot selection has been markedly worse in the NCAA Tournament, about 1-2% worse than what I would’ve personally expected.

And yet: the two-point shooting hasn’t really been the problem. Even despite this downgrade in shot selection, the 2022 NCAA Tournament has produced a 2PT% of 47.9%. That’s down from the last several Tournaments, sure, but it’s also a superior 2PT% to 14 NCAA Tournaments from 1987 to now. In fact, this has more or less been an average Tournament from a two-point perspective. Teams are missing a few more shots at the rim than usual, but it’s been counterbalanced somewhat by about a 0.5-1% over-performance on mid-range twos, per the CBB Analytics data. To sum it up: the shot selection has been bad, but it hasn’t really been the entire reason for this Tournament’s offensive car crash.

Is it the ball?

An issue I think that is crazy in college basketball is the variance in basketballs used: Adidas, Nike, Wilson Evo NXT (NCAAT), Old Wilson Evolution, and Spalding TF-1000. [With regards to the Evo NXT], these balls are pumped up and not broken in for March throughout the season.

This is, by some measure, the hardest one to prove or disprove. I am not there in person feeling the basketball itself, so I cannot tell you if it feels like an outdoor ball or it’s hard to get in a rhythm with. Several reviews online believe this ball to be an upgrade over the previous model (Wilson Evolution), which is the ball I own and love. Considering that basically nobody used this ball in games from November to early March, though, it makes the below trendline pretty troubling.

68 NCAA Tournament teams, regular season, various balls: 35.1% 3PT% on 47,767 attempts

68 NCAA Tournament teams, 2022 NCAA Tournament, Evo NXT ball: 31.5% 3PT% on 2,674 attempts

Now, it’s worth noting that in most NCAA Tournaments, there’s an underperformance of about 1-2% from regular season to postseason. You can explain this in various ways, all of which we’ve tried in the past: better defenses, tougher competition, higher stress, unfamiliar venues. All of those are reasonable. But: to be underperforming that regular season rate by 3.6% is a serious outlier. Did any team foresee this coming?

The only way I can imagine testing this, and it is extremely silly, is to use Getty Images to our advantage. I looked through photos of every team in the field from November to March, looking to see which ones used the Evo NXT in any game this season. (Inspired by a New Mexico State fan sharing a photo from January.) Is this unscientific? Yes, and it leaves smaller schools at a serious disadvantage, because photographers aren’t at their games as frequently. But what other way can you really test this that isn’t me telling you this is the worst 3PT% ever and a massive delta from the regular season?

Of the 68 teams in the field, I could confirm, via at least one photo, that 25 teams used the Evo NXT ball either in the regular season, their conference tournament, or both. That’s just 37% of the field using the ball that 100% of the field uses for three weeks in March, which seems less than ideal. If you split out the 25 teams who did have photographical evidence of experience with the ball versus the 43 who didn’t, here’s how it shook out:

- Did use the Evo NXT ball prior to the NCAA Tournament: 283-for-894 (31.7%)

- Didn’t use the Evo NXT ball: 560-for-1780 (31.4%)

Uh…well, that’s all of a 0.3% difference. It’s more that everyone isn’t shooting well versus just the teams that had no experience. Still, I think there’s a great point to be made here. Why are we entering the NCAA Tournament with a ball that over half the field seems to have not used in a game? Why can college basketball not agree on one, or at most two, standardized balls to use over the course of a season? The answer, as always: money.

Is it simply a sample size issue?

No coach or media member mentioned this theory, which is completely fine. All of the five theories above were interesting and worth researching. However, it’s a question I have to ask myself: would I be worrying this much about March Madness if this same sample of play happened over two weeks in November?

All you have to do is look back to the first three days of the season, in fact.

- November 9-11: 31.6% 3PT%

- NCAA Tournament: 31.5% 3PT%

But that sort of obscures what we’re talking about here. The trendline of a season’s 3PT% goes up from November to March, and true to form, the last three days of the regular season (March 4-6) saw teams shoot 33.9% from three, which is 2.3% higher than they did in the first three days of the season. So why would it bottom out, seemingly out of nowhere, at a time when teams should be shooting better than usual?

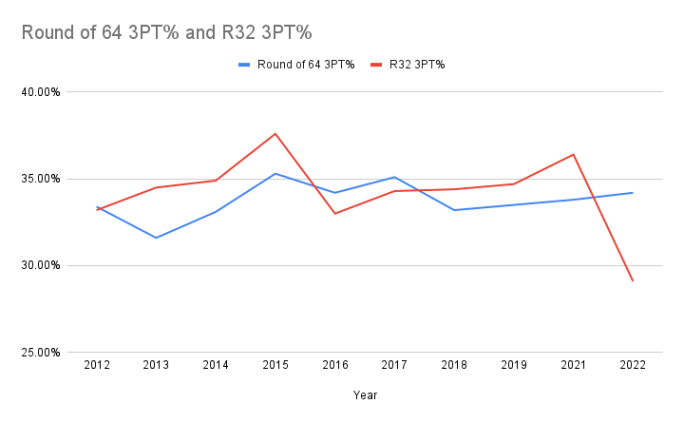

If you just watched the first round of the 2022 NCAA Tournament, you wouldn’t imagine that much of anything was wrong at all. Teams shot 34.2% from deep, about 0.5% above the average of the last 10 years. That’s not a huge leap, but it was surprising. The regular season’s 3PT% of 33.7% is the second-lowest ever since the NCAA began tracking threes at the introduction of the three-point line in 1986-87. This is undoubtedly due to the NCAA moving the three-point line back. The three seasons before the line was moved back a foot: 34.8% from deep. Last three seasons: 33.6%. So there’s that.

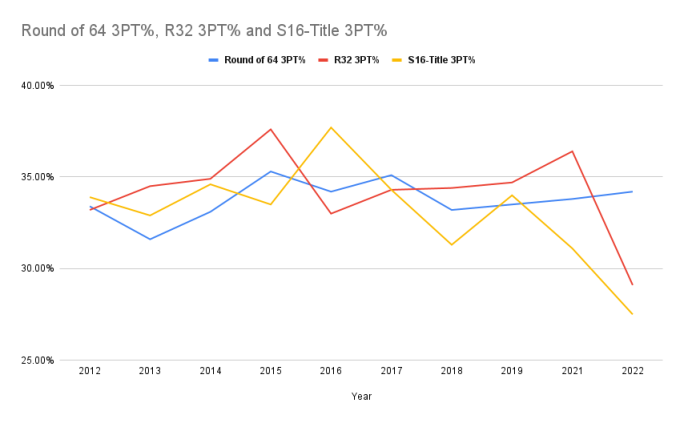

But that alone still wouldn’t explain what’s happened, starting in the Round of 32. Across the nine Tournaments directly preceding 2022, teams shot 1.1% better in the Round of 32 than they did in the Round of 64. This has a pretty simple explanation, to me: better teams are alive, and said teams are playing their second game in the arena of a weekend. You’re more familiar with your surroundings. That did not happen this year. In fact, it gave us the worst Round of 32 3PT% performance I can find on record.

Teams shot 29.1% in the Round of 32 this year, the worst single-round performance of either of the first two rounds I was able to find. That, obviously, is not ideal. To go with this, teams have shot about 1.1% worse from deep from the Sweet Sixteen onwards. There are multiple explanations for this that all make sense to me: different venues, tougher defenses, more stress, etc. But it’s still hard to explain the 2022 teams shooting 27.5% from deep in the Sweet Sixteen and Elite Eight.

With the trendlines looking the way they look, one of two things seem like they can happen this coming weekend:

- It gets worse. The remaining Final Four teams are now moving to another different arena, their third in three weeks. Teams will have likely never shot at this arena before arriving. What’s turned into a truly disastrous shooting performance remains disastrous, as the Final Four teams (expected to shoot 36.1% on threes based on season-long numbers) shoot 32% or worse.

- It really is a sample size issue and regresses to the mean. You can’t judge everything off of 24 games of data, and the Final Four teams have a reasonable outing in line with previous NCAA Tournament trends: roughly 34-35% from deep across the three games.

Either answer will give us more theories, which leads us back to the initial question of why this happened, which then starts the debate(s) all over again. Have we learned anything? I’m not so sure. But I look forward to learning how this closes up this weekend.